What 2026 will demand from purpose-driven organisations and high-performing teams.

There is a sentence I hear more often than any other when I sit down with leadership teams: We need to become more adaptive. It comes from CEOs, CHROs, transformation leads, and managers alike. Sometimes it is spoken with a kind of urgency, sometimes with some weariness, but almost always with true conviction.

Adaptability has become a key capability for organisations heading into 2026. Not because it is fashionable and sounds great, but because the ground beneath organisations continues to shift. AI adoption is accelerating. The market for attracting the right talent is limited. Customer expectations change far quicker than internal structures can keep up with. And the geopolitical and regulatory uncertainty continues to loom. Standing still is not an option for any organisation that aims for sustainable growth.

Yet, what strikes me most is not the ambition to adapt. It’s the widening gap between what organisations want to achieve and what their systems, leadership, and teams can actually support. To me, that gap is not technological. It is human.

Why adaptability dominates the 2026 agenda

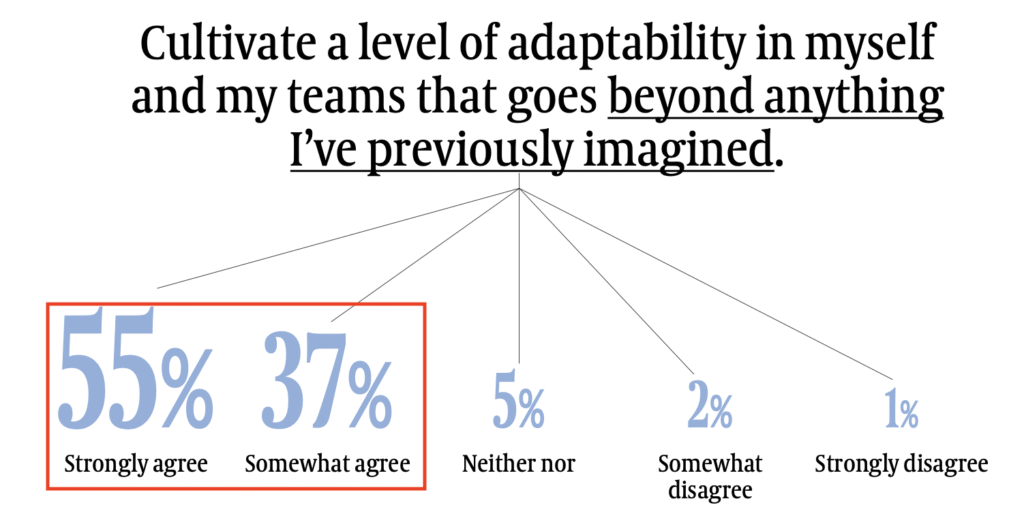

Recent leadership research makes this unmistakably clear. Egon Zehnder’s latest global CEO research shows that being adaptable and agile is crucial for future success. Most CEOs agree that the next phase of leadership demands a level of adaptability like never before.

This is also what I see in practice. Leaders know that the rules have changed. Long planning cycles are no longer perceived as the holy grail. Static operating models, more often than not, struggle under continuous disruption. The ability to respond, tweak, and realign has become essential.

The same research also highlights an interesting gap: many see adaptability as vital, but fewer organisations feel cconfident to live up to this. Let’s also take a look at the recent Business Agility 2025 report. This indicates that overall maturity remains steady. Mind you, it would be good to note that the rate of improvement has slowed down considerably. Where it once took just over two years to achieve a meaningful uplift in adaptability, organisations now need a period that is close to four years.

This is not because organisations have stopped investing. It is because adaptability has moved from being a structural challenge to a systemic one. The easy wins are more or less behind us. What remains requires deeper shifts in how leaders lead, how teams work, and how decisions are made.

The real obstacle is not strategy but behaviour

A common myth about adaptability is that it’s mainly a strategic or structural problem. Change the model, introduce new frameworks, and redesign the organisation chart. Then, adaptability will follow. Right?

In reality, adaptability lives in behaviour. It shows up in how leaders act under pressure, how teams find clarity or confusion, and how decisions are made when trade-offs arise.

The Business Agility Institute’s 2025 report makes this also painfully visible. Under pressure, organisations often revert to familiar habits. Decision-making becomes centralised. Governance gets stricter. Silos become more rigid. Learning loops shorten. Leaders do not aim to hurt the organisation’s adaptability. Instead, pressure changes how they see things.

What makes this particularly difficult is that many organisations still lookadaptive on the surface. Most of these organisations are Doing Agile instead of Being Agile. They use the right language. They have adopted modern ways of working. But the system and underlying behaviours struggle when conditions tighten. Adaptability becomes theatrical rather than lived. For more on this, see also my related article: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-your-agile-change-feels-like-theatre-alize-hofmeester–c8zme/?trackingId=zL4XdDW7S2ysPxPXE7nXHw%3D%3D

This is where human capability becomes the roadblock. Not just skills, but also emotional steadiness, trust, and shared confidence. When leaders don’t have time to reflect, teams feel the pressure of shifting priorities. Trust can start to fade, which slows down adaptability long before it is acknowledged.

Trust and engagement are early warning signals

Some of the recent research shows a strong link between adaptability and engagement. The Business Agility 2025 report, based on Glassdoor data, highlights a clear difference. Organisations with rising adaptability enjoy much higher employee advocacy and positive sentiment. In contrast, those with falling adaptability face significant declines.

Trust, it turns out, is not a “soft” outcome of adaptability. It is a prerequisite.

Gartner’s 2025 data confirms this. Nearly 79% of employees report low trust in change leadership. That does not mean people resist change by default. It means they no longer feel confident that change is being led in a coherent, transparent, and people-centric way.

When trust declines, adaptability starts to suffer. Think of teams that hesitate or leaders that over-explain or over-control. But also decisions slow, not because people are unwilling, but because they are unsure. And the paradox is that the system becomes increasingly cautious at exactly the moment it needs to move.

AI will amplify what is already true

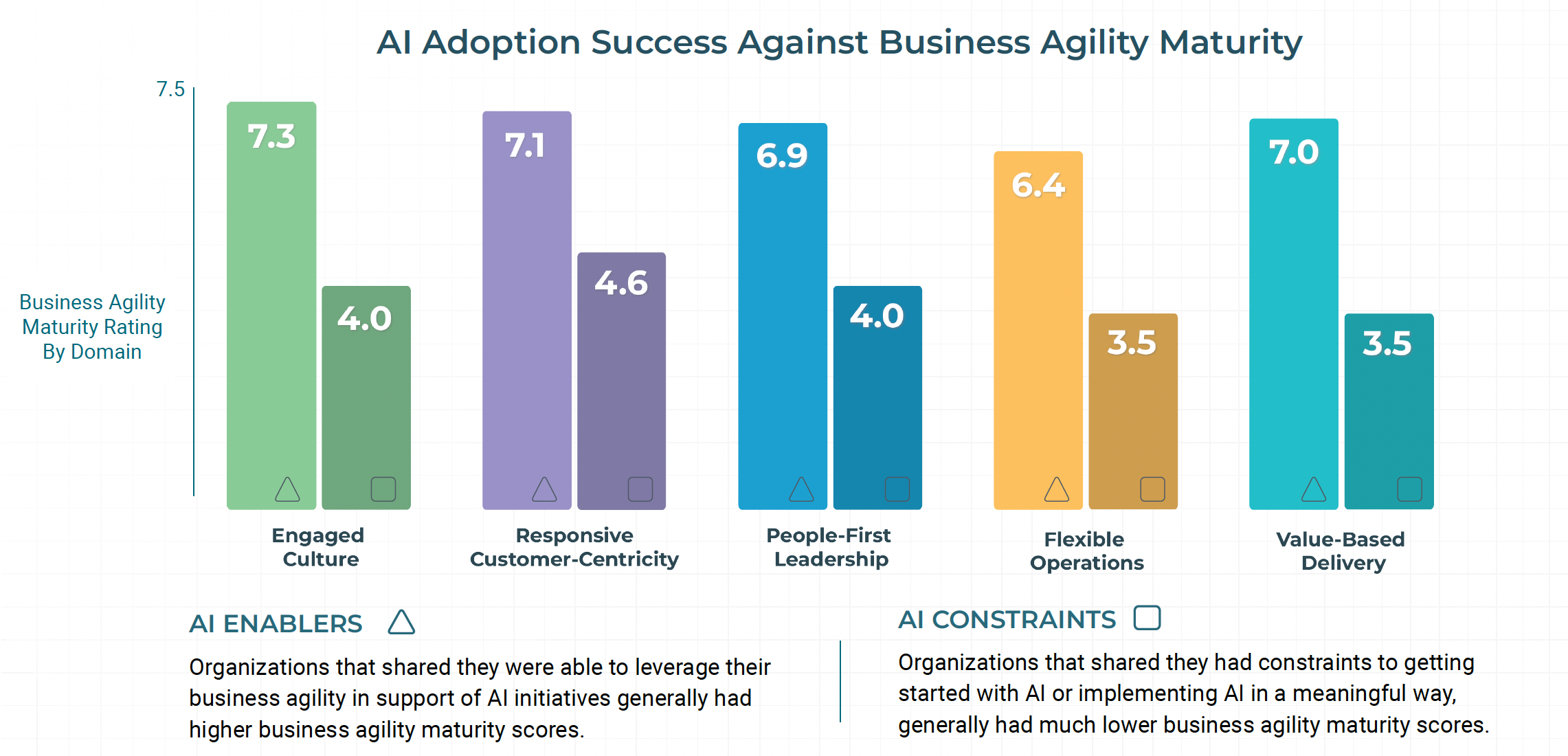

AI is often positioned as the next great accelerator of organisational performance. And it can be. Though the 2025 Business Agility Institute report raises a key question: does being adaptable help with successful AI adoption, or does AI itself boost adaptability?

The data suggest the first. Organisations that are more adaptable see much better results in AI implementation compared to those that are less mature.

This finding aligns with what I see as well: AI does not fix organisational dysfunction. It amplifies it. Where transparency is not visible, AI raises the feeling of distrust. Or where decision-making is unclear, AI increases confusion. Where trust is low, AI fuels anxiety. And where leadership is reactive, AI accelerates fragmentation.

In organisations with strong leadership, clear decision-making, and effective learning loops, AI can be a major advantage. It enhances speed, the gaining of insights, and value creation because the human system can absorb and direct it.

The implication for 2026 is profound. Investing in AI without investing in human capability is your risk multiplier.

What purpose-driven, high-performing organisations do differently

What I note about organisations that continue to adapt under pressure is that they share a number of characteristics. Not because they are exceptional, but because they have made deliberate choices about how they operate.

- They reduce strategic noise. Instead of piling initiative upon initiative, they make hard choices about focus. They actively stop doing things. This creates cognitive and emotional space for teams to do meaningful work.

- They clarify decision authority. People know who decides what, under which conditions, and with what input. This reduces uncertainty and builds confidence, even when decisions are difficult.

- They invest in leadership steadiness. Leaders are expected not to just deliver outcomes, but to regulate the pressure. This makes the system stable.

- They build rhythm. You know I’m a big fan of this. Regular moments for alignment, reflection, and learning are maintained, even under stress.

- They treat purpose as a guide for behaviour and not as a slogan.Purpose informs priorities, trade-offs, and choices, especially when conditions are uncertain. This creates better coherence across personal, team, as well as organisational levels.

What links these organisations is not perfection, nor the absence of pressure. It is the conscious choice to design for adaptability rather than demand it. They accept that high-performance is not created by squeezing more out of people.

Instead, they create conditions in which people can think clearly, decide responsibly, and move together. In this context, purpose becomes more than an aspiration. It serves as a stabilising force. It helps leaders and teams handle uncertainty while staying focused. And that is what allows performance and people-centricity to reinforce each other instead of compete.

Five steps to strengthen organisational adaptability in 2026

If adaptability is key for 2026 and human capability is the challenge, our work will be practical and personal. Based on what the data shows and what I see in organisations, these five actions can make a tangible difference.

- Make trade-offs explicit. Unspoken trade-offs drain trust. Leaders who name what they choose not to pursue create clarity and reduce silent overload.

- Redesign decision flow, not just structure. Map where decisions slow down and remove unnecessary handovers. Speed is created by reducing friction, not by adding pressure.

- Develop leaders as system stabilisers. Leadership development has to go beyond skills and tools. Emotional stability, self-awareness, and the ability to manage pressure are now core capabilities.

- Strengthen team conditions before raising expectations. Teams adapt when they have clarity, psychological safety, and real autonomy. Without these, adaptability remains nothing more than a nice, fancy theory.

- Reconnect purpose to daily work.Purpose shapes how we set priorities, define success, and find meaning in the contributions we make. Especially when work becomes harder.

None of these actions are quick fixes. But together, they create the conditions in which adaptability becomes sustainable rather than exhausting.

Heading into 2026

I’m confident that adaptability will continue to dominate leadership conversations in 2026 and beyond. But organisations that truly adapt will not be those that should about it. They will be the ones that invest quietly and consistently in human capability.

The data is clear. Pressure is not going away. AI will accelerate complexity. Trust will become a differentiator. And leadership behaviour will matter more than ever.

The real question for leaders is not whether their organisation wants to be adaptive. It is whether they are willing to do the deeper work that makes adaptability possible. Because in the end, adaptability is not something an organisation has. It is something people live, every day, together.